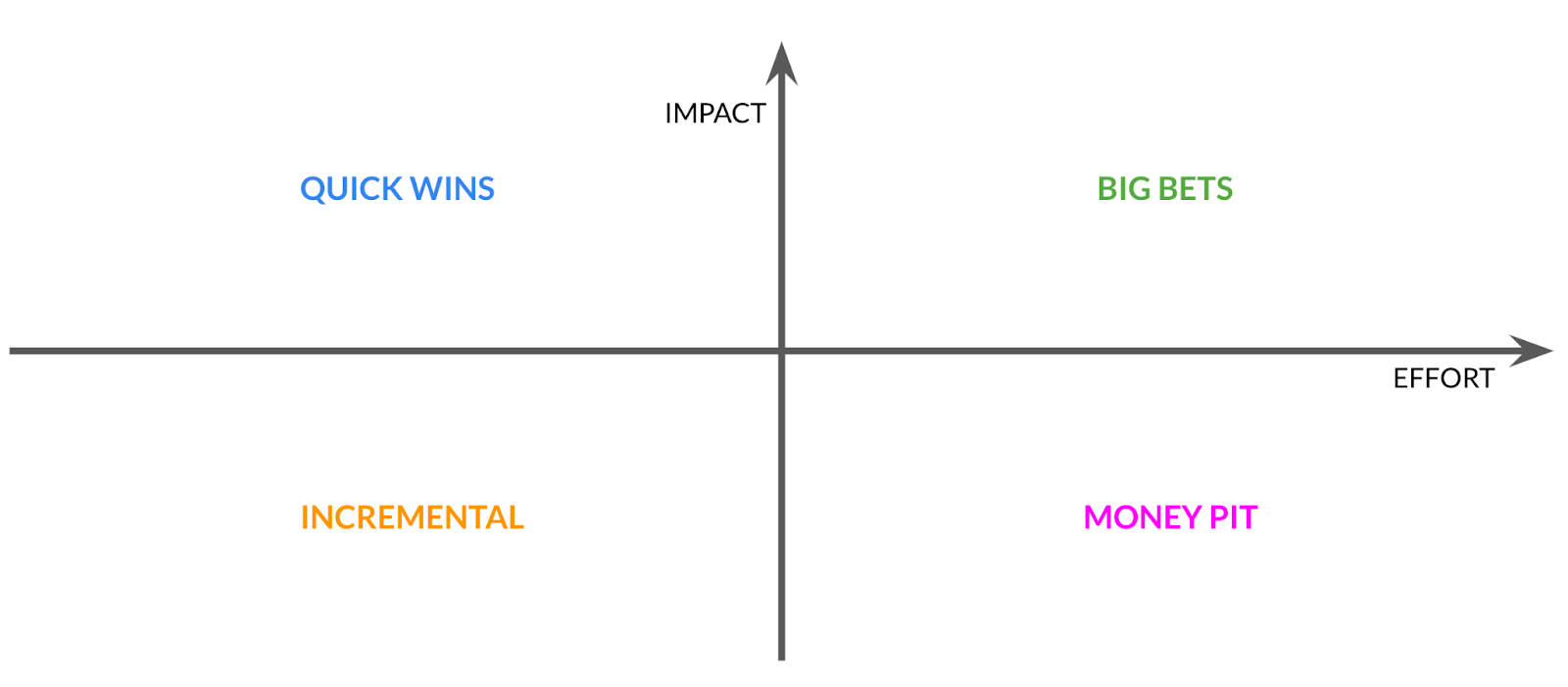

I hear the phrase ‘low-hanging fruit’ all the time in organisations. That’s because it’s become synonymous with the ‘Quick Wins’ quadrant of the Impact/Effort’ matrix - valuable ideas that are the quickest and easiest to deliver. During a recent talk at Product Tank Manchester, I asked an audience of close to 100 people if anyone in the room hadn’t used that matrix to prioritise their roadmap. Not a single person raised their hand.

Figure 1: The ubiquitous ‘Impact/Effort’ matrix

In this article, I’ll challenge the primacy of ‘low-hanging fruit’ by critically re-examining the related concept of marginal gains, before proposing that a better understanding of product debt will help organisations thrive in the post-pandemic world.

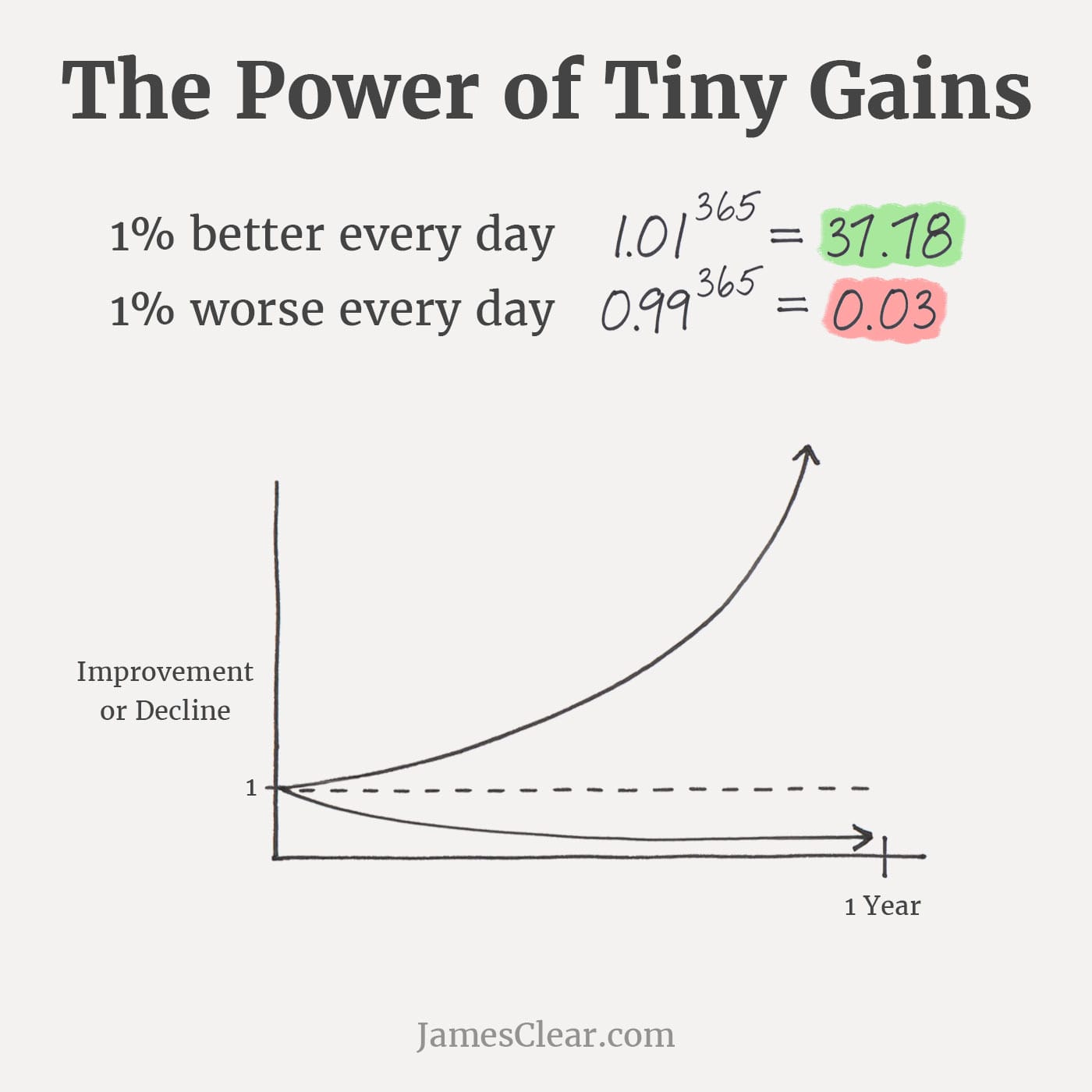

‘Marginal Gains’ is a type of low-hanging fruit. The theory came to many people’s attention in the 2018 book Atomic Habits, in which James Clear proposed a radical new idea: that performance could be significantly enhanced through the implementation of a large number of small changes. He calculated that if you improved something by 1% every day, after a year, you’d be 37 times better than when you started.

Figure 2: The classic way to illustrate the concept of Marginal Gains

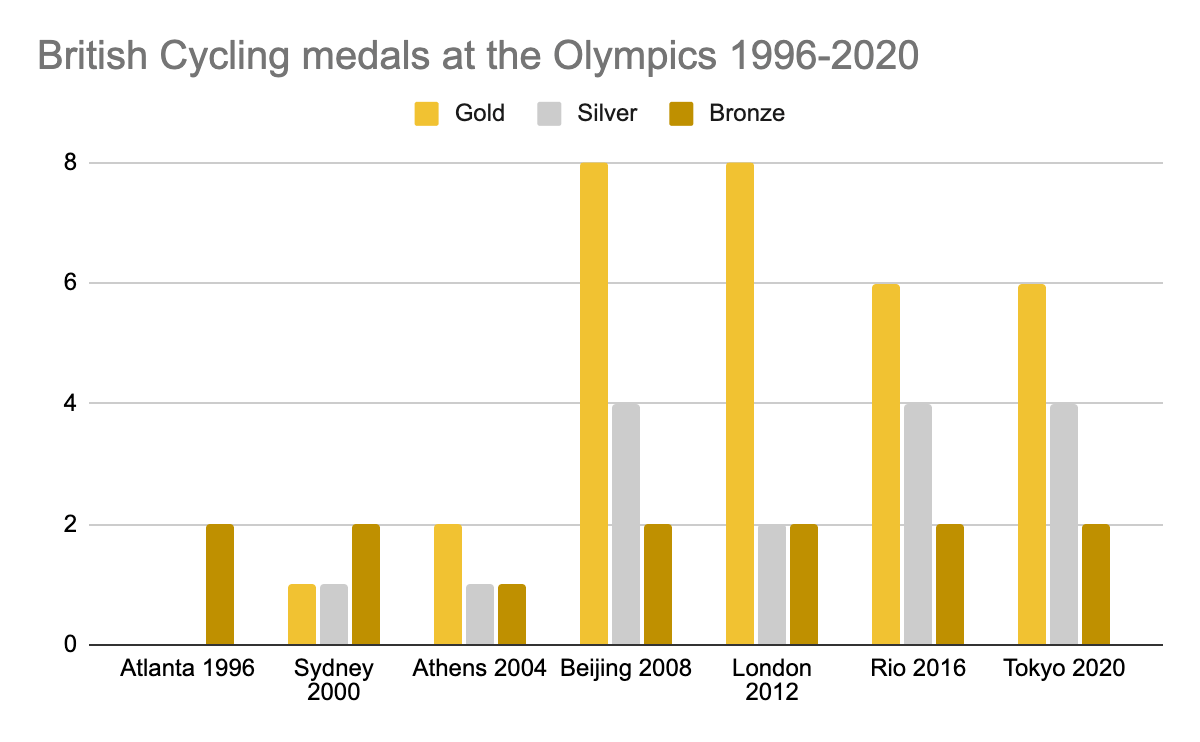

Clear used the example of British Cycling to explain how marginal gains could deliver incredible, unprecedented success. If you’re unfamiliar with the story of Marginal Gains and British Cycling, here’s a brief overview.

Between 1896 and 1992, the British cycling team only won one Olympic gold medal (in 1908). In 2003, they hired a new performance director, Dave Brailsford, who brought with him a hypothesis: if the team made small improvements to a large number of things, it would result in a massive cumulative effect.

These improvements included (but were not limited to) such things as rounder wheels(!), upgraded seats, uniforms and helmets; new pillows and mattresses for riders to help them sleep; and a ‘no handshakes’ policy, to slow the spread of germs.

Following Brailsford’s first full Olympic cycle, Team GB topped the medals table, and have stayed there ever since. Coupled with his work on the road with Team Sky (later Team Ineos), which resulted in seven wins at the Tour de France in the eight years, Brailsford has helped Britain become, by any measure, the most successful cycling nation in the world.

Figure 3: The ‘before and after’ picture of Olympic success for British Cycling

The story of how British Cycling owed its success to marginal gains has proved so persuasive that it has entered the popular imagination. There are now countless articles on how the theory might be applied to everything from weight loss to Agile software delivery. It’s likely to have gained such traction in the world of Agile for two reasons. Firstly, it provides a deceptively simple answer to a difficult question: how do I make significant, long-lasting changes to my business, one small step at a time? And secondly, the concept dovetails nicely with the language of the Agile Manifesto, with its repeated emphasis on continuous, incremental improvements:

(my emphases added)

Delivering small amounts of value early and often, on a cadence that can be maintained indefinitely, sounds a lot like ‘1% better every day’. Indeed, the two concepts have become inextricably linked in the tech space.

Returning to the origin story of British Cycling, any sceptic looking at Figure 3 would have to accept that Dave Brailsford applied the theory of Marginal Gains and achieved remarkable things. It stands to reason that if those principles were applied elsewhere, similarly impressive results could be enjoyed. Unless there’s more to the story of than meets the eye…

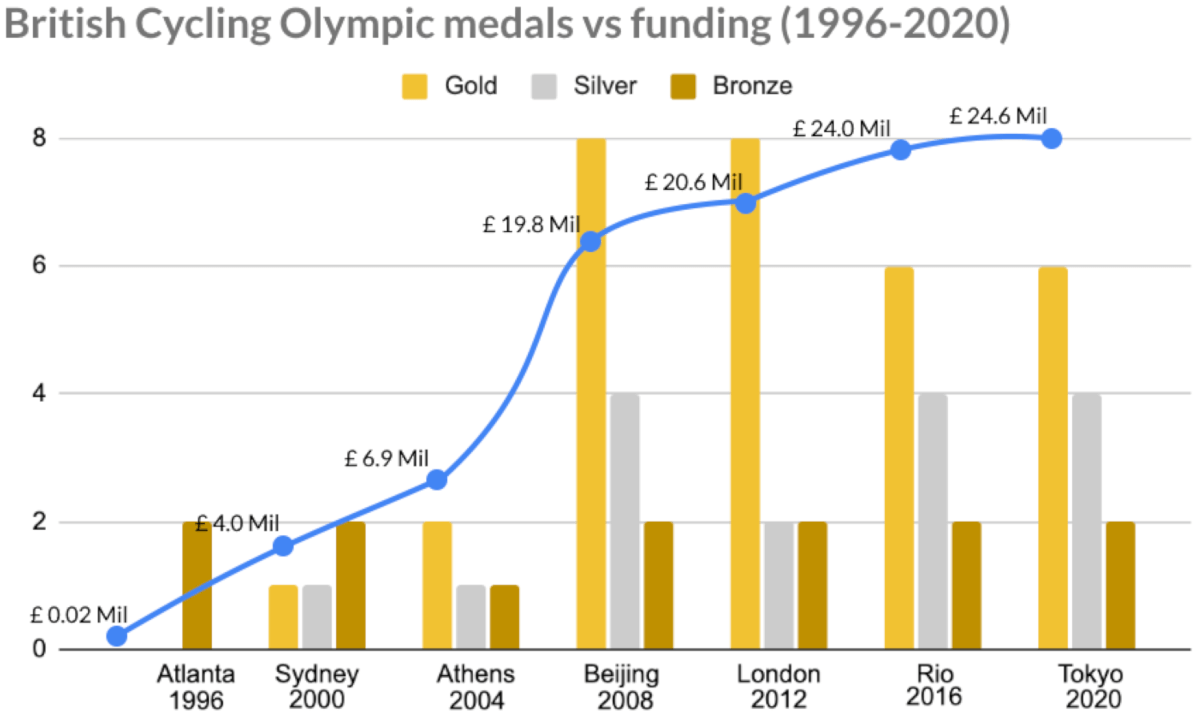

Between 1994 and the 2000 Olympics, the budget for British Cycling increased by 175 times, from £20,000 to £3.9m a year, due to National Lottery funding becoming available for the first time. By 2008, when Team GB hit the top of the medals table in Beijing, the budget was 1000 times greater.

That money was invested in such things as:

By any measure, these aren’t ‘marginal improvements’ - they're massive, sustained investments. Elite cycling is an expensive sport, with high barriers to entry. For example, a single Olympic bike costs upwards of £30,000. On average, each rider in the British team has three bikes. There were 26 riders at the Tokyo Olympics, which equates to £2.3m in bikes alone. Most countries simply cannot afford to compete at this level.

The totemic example of Marginal Gains - British Cycling’s success at the Olympics and on the road since 2008 - cannot only be explained by the cumulative effect of tiny improvements over time. Instead, it is largely if not entirely down to a huge and sustained injection of capital, as shown by this chart tracking medal performance against funding.

Figure 5: Funding vs Performance for British Cycling

Why is it important to critique the ‘Impact/Effort’ matrix? Why debunk the origin myth of marginal gains?

I believe it’s important because unthinkingly prioritising low-hanging fruit, whilst pursuing marginal gains, leads to product debt. I call it that because it sounds like (and is like) tech debt - so when talking about it with other members of a delivery team, there’s a shared frame of reference.

Product debt is the consequence of consistently following the path of least resistance when making decisions - choosing quick, imperfect wins whilst ignoring or deferring difficult decisions about the hard stuff. Product debt creates an obligation that accrues interest over time, that the organisation will eventually have to confront.

Left unaddressed for long enough, product debt becomes a dysfunction so profound that it’s impossible to correct without completely throwing away what you have and starting again from scratch. In other words, when product debt grows too large, you can’t pay it down. You can only write it off.

Product debt most commonly occurs when speed and ease over-index as key metrics for an organisation. Quick wins, in the form of small, incremental improvements, become the order of the day.

Running high volumes of concurrent, low-impact experiments that typically don’t work and have to be thrown away is no longer good enough. After a pandemic-fuelled boost, the post-Covid reality is that tech budgets and team sizes are either frozen or in decline. Organisations need to find ways to do more with the same or less. Continuing to try and live on a diet of low-hanging fruit is a low-risk, low-reward strategy that is also inherently, fundamentally wasteful - and means that many organisations are trapped in an underwhelming pattern, slowly going nowhere.

I believe that the Product community has a critical role to play in helping organisations achieve ‘strategic efficiency’. Rather than continuously exploring an unlimited number of small ideas, and expending heroic effort without commensurate returns, we must instead be systematic when assessing which problems we are going to try and solve. It won’t be easy, but the future of Product relies on us placing precision before profligacy.

The answer is for Product to articulate ‘fewer, but truer’ business cases that address the most valuable problems in the organisation, regardless of difficulty. And by most valuable, I mean those that will deliver the best Return On Investment (ROI). British Cycling didn’t become successful by making hundreds of 1% improvements. Instead, it invested heavily and sustainedly in the best athletes and equipment, and surrounded that team with a world-class support infrastructure. They chose where to invest by analysing data from potential athletes, then ruthlessly reduced the team down to a handful of the very best riders who could win medals. This is the lesson we should be taking from their story.

Low-hanging fruit, quick wins, marginal gains - these ideas have been the orthodoxy for Product for too long, and it’s time for us to change it.

Comments

Join the community

Sign up for free to share your thoughts