If you’re shy, struggle to make conversation and ever find yourself at a party with some product managers around, ask them about their favourite tools and frameworks. Chances are, from that point onward, they will not only do all the talking for you but will also thoroughly enjoy the conversation. Product managers love their tools and frameworks. We love them because they support us in our everyday jobs and often serve as useful shortcuts and structured approaches that help us solve problems and make decisions quickly. That is… if we use them correctly.

A stakeholder map is one of those handy aids; it’s a useful tool that can make your stakeholder management more effective. When done well, it helps you see at a glance what stake people, teams or whole departments have in your product and how you should therefore manage the relationships with them.

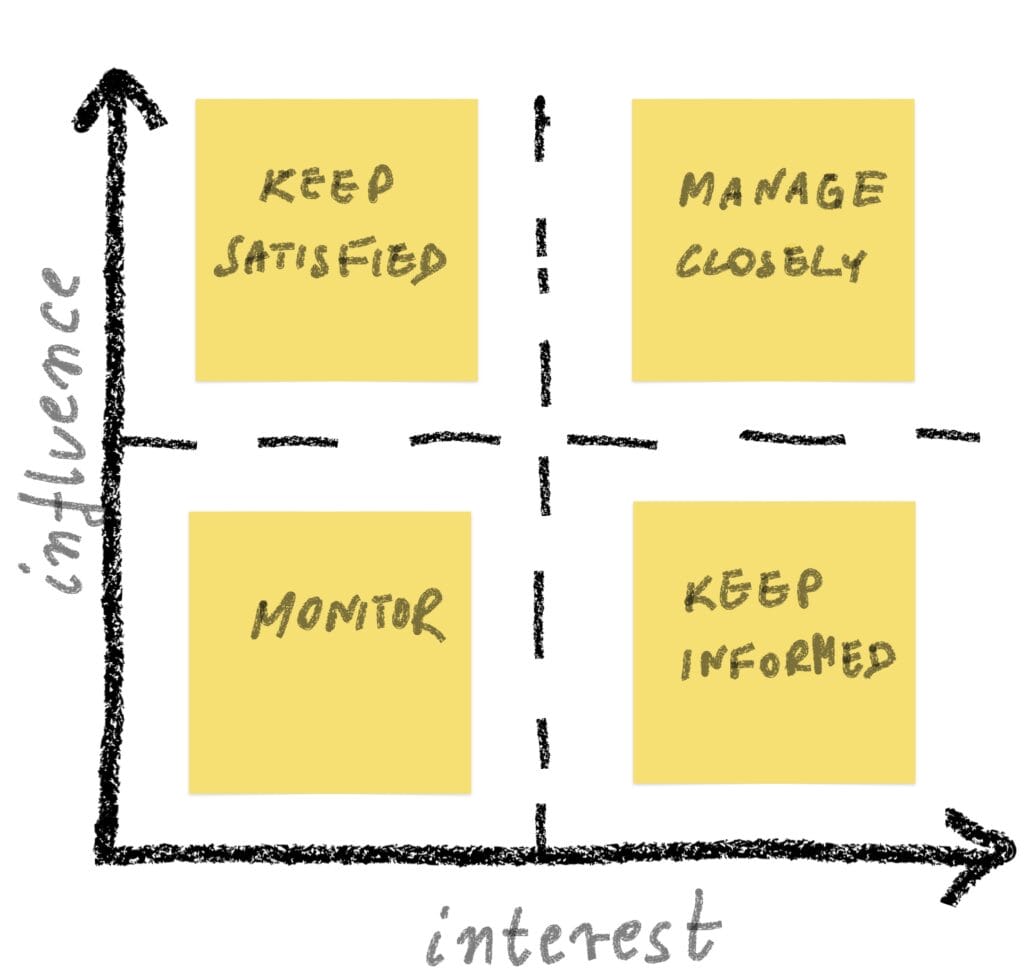

My favourite stakeholder mapping model is the interest and influence matrix. This is where you identify groups and individuals in the organisation that you should manage carefully because they not only have a stake in your product but can also decide about its fate (high influence, high interest). Then there are those you should keep satisfied because of how influential they are in the organsiation, even though they might not have a high level of interest in your product; those you should monitor from afar and those you should actively keep informed.

There is no shortage of advice available on how to create stakeholder maps, so instead, let's focus on three common mistakes product managers make when using this tool.

We tend to create stakeholder maps when beginning a new journey, e.g. starting a new job, moving into a new role or managing a new product. There’s a flurry of enthusiasm and activity as we want to learn as much as possible about the environment around us and so naturally this is the time when we are most likely to create many product management artifacts.

But as time flies, we get comfortable in our ways. Suddenly, it’s month ten and a blink later it’s year two on the job. The reality and the constant context-switching take over, and we rarely revisit the documentation we used at the beginning.

The problem is that companies and products never stay the same. There are constant changes we might not have noticed that render our stakeholder map out of date. There are bigger shifts, such as when people join and leave the organisation or when whole departments refocus on a new priority. And there are smaller, more subtle changes, e.g. a really engaged stakeholder you used to meet for a chat every two weeks might have a broader remit now than she used to, which affects her ability to impact your product and/or her level of interest. If you don’t adjust, the relationship will become ineffective.

For a stakeholder map to be actually helpful and not just yet another shiny artifact, it needs to be up-to-date. Always. Otherwise you risk creating misalignment, which in turn may lead to conflicts, delays, and dissatisfaction.

Creating a stakeholder map is not a goal in itself. You create one to appreciate the context around your product, to better understand the objectives of the various stakeholder groups and how they influence your product.

However, one of the most useful applications of stakeholder maps is to support your communication strategy. It’s a fantastic model that helps you tailor your message, channel, timing and frequency of communication to the right audience. How often do you engage with individuals or groups that you need to “manage closely” vs “keep informed”, what level of detail your messages should contain depending on the audience, whether you should seek quality interactions 1:1 or simply broadcast your update via a Slack channel. All these decisions become easier if you base them on a stakeholder matrix.

And yet what often happens is that we repeat existing communication habits, carrying on with many ineffective meetings just because they’re in our diaries, or having 1:1s with people who have long lost interest in our product while neglecting new groups of influence. Over time, our stakeholder relationships will suffer, which in turn will affect internal support for the product.

Ironically, this is a mistake often made by more experienced product managers. Once you have a number of years of experience to back you up, drawing a stakeholder map may seem redundant. After all, you know the business really well, you could manage your stakeholders in your sleep and you have been consistently delivering products.

Here’s the thing though: chances are you are working on autopilot, rarely revisiting your ways.

“When we talk about “being on autopilot” as human beings, we’re talking about the functions we rely on because they are such ingrained habits in us—like when you drive home only to step out of your car and barely remember anything about your commute.”, writes Carey Lohrenz in Forbes (“Autopilot: Your best friend and your worst enemy”, Forbes, 10 August 2021).

There may be nothing wrong with using autopilot most of the time: The fact that you’re not reconsidering every single step along the way means you can prioritise focusing on new challenges which require more of your brain power.

However, just like it becomes harder to notice anything different along the way when you drive down the same road time and time again, when working on autopilot, you are likely to pay less attention to the changing context around you.

It’s worth checking you really understand the stakeholder landscape as well as you think you do. I guarantee you’ll discover something new or maybe even surprising if you draw out your stakeholder map. Override your autopilot once in a while!

Remember, while tools and frameworks are fantastic aids, it's all about how you use them. By avoiding the three mistakes above, you can tackle even the most difficult stakeholder relationships and complexities.